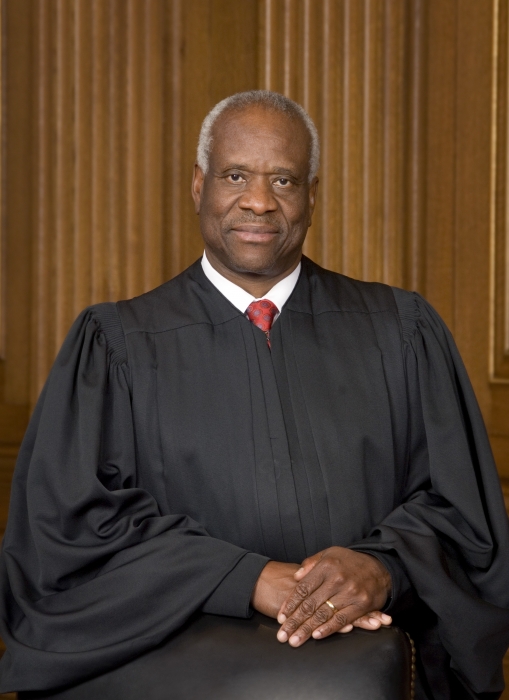

Clarence Thomas has taken strong positions on speech protections under the First Amendment, defending commercial speech and railing against campaign finance restrictions as restrictions on political speech and association. (Photo via The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States, public domain)

Justice Clarence Thomas (1948– ) has at times surprised observers with his bold, independent vision on First Amendment issues. Thomas has served on the Supreme Court since 1991 after undergoing highly publicized and controversial confirmation hearings,

Although detractors have derided him for his relative lack of prior judicial experience, his silence during oral arguments, and his alignment in many cases with Justice Antonin Scalia, Thomas has proved to be a strong defender of First Amendment free expression rights in several contexts, often applying an originalist method of interpreting the Constitution. He published an autobiography, My Grandfather’s Son (2007), that tells his story.

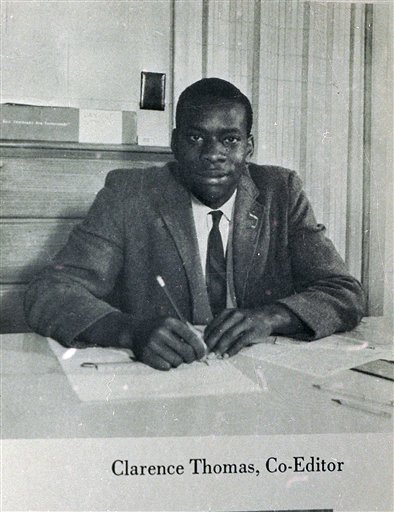

Born in Pin Point, Georgia, Thomas was raised by his grandparents. He worked his way through college, earning an undergraduate degree from the College of the Holy Cross and, in 1974, a law degree from Yale Law School.

After graduation, he worked as an assistant attorney general in Missouri for several years and then for two years for the Monsanto Company. In 1979, he became a legislative assistant for Sen. John Danforth, who later backed Thomas when he was nominated to the Supreme Court.

In 1981, Thomas served in the Department of Education as assistant secretary for civil rights. The next year he became chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), a position he held until 1990, when President George H. W. Bush appointed him to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

One year later, after the death of Justice Thurgood Marshall, President Bush appointed Thomas to the Supreme Court. During Senate confirmation hearings, he survived charges of sexual harassment by Anita Hill, a law professor, who had worked for Thomas at the EEOC. He won confirmation by a narrow margin, 52-48, and became the second African-American to serve on the Court (Marshall was the first).

Clarence Thomas was a Supreme Court Justice who at times surprised observers with his bold First Amendment stances, such as his questioning of the Court’s interpretations of the establishment clause. This photo is of Thomas during his time as chairman of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission in 1984. (AP Photo/John Duricka, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Since 1991 Thomas has taken several strong positions on the First Amendment, calling for the Court to overrule precedent.

Jan Crawford Greenburg, author of Supreme Conflict: The Inside Story for Control of the United States Supreme Court, wrote in the Wall Street Journal that Thomas was an independent voice from the beginning. “His brutal confirmation hearings only enforced his autonomy, making him impervious to criticism from the media and liberal law professors.”

In one of his more significant opinions, Thomas clarified the content discrimination principle in Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015). Thomas emphasized that a law is content-based if it draws any distinctions on speech based on content – even if the underlying purpose of the law is not to suppress speech or viewpoint.

“A law that is content based on its face is subject to strict scrutiny regardless of the government’s benign motive, content-neutral justification, or lack of ‘animus toward the ideas contained’ in the regulated speech,” Thomas explained.

Thomas has been a staunch defender of commercial speech, arguing that truthful commercial speech should not receive less protection than other forms of noncommercial speech, such as political speech.

In a concurring opinion in 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island (1996), Thomas wrote that the Court should abandon its ruling in Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), which subjects restrictions on commercial speech only to intermediate scrutiny.

Thomas believed that bans on truthful commercial speech should be subject to the rigors of strict scrutiny. He wrote in an oft-quoted passage: “I do not see a philosophical or historical basis for asserting that ‘commercial’ speech is of ‘lower value’ than ‘noncommercial speech.’ Indeed, some historical materials suggest to the contrary.”

He reiterated his strong stand on commercial speech in his dissent in Glickman v. Wileman Brothers and Elliott, Inc. (1997) and in other opinions.

Clarence Thomas is seen in a high school year book photo, circa 1959. In his time on the Court, Thomas has been has been a staunch defender of commercial speech, arguing that truthful commercial speech should not receive less protection than other forms of noncommercial speech, such as political speech. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

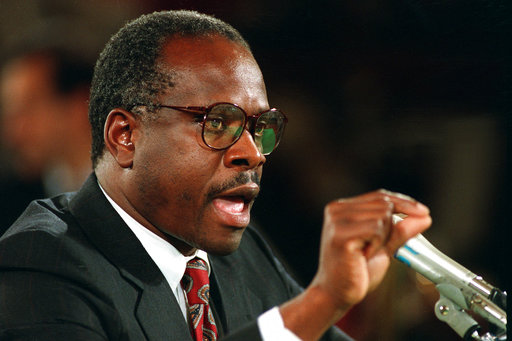

Thomas has consistently railed against restrictions on campaign finance as grossly unconstitutional restrictions on political expression.

Most notably in his partial dissent in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003), he wrote that “the Court today upholds what can only be described as the most significant abridgment of the freedoms of speech and association since the Civil War.”

He wrote that the “Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (BCRA), directly targets and constricts core political speech, the ‘primary object of First Amendment protection.’ ”

Thomas wrote separately in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), ruling that even the disclaimer and disclosure requirements of the BCRA are unconstitutional. Previously, in other opinions Thomas had called for the Court to overrule its seminal campaign finance reform decision, Buckley v. Valeo (1976), and subject all such laws to strict scrutiny.

In free expression cases, Thomas filed a lone dissent in Avis Rent a Car System, Inc. v. Aguilar (2000) when his colleagues refused to review a California Supreme Court decision that upheld an injunction limiting an employee from speaking certain racially derogatory words in the workplace. Thomas warned that the “unprecedented injunction” in the case “very likely suppresses political speech.”

He provided the decisive vote in United States v. Playboy Entertainment Group (2000), in which the Court invalidated a federal law that required cable television operators to scramble sexually explicit programming. Thomas wrote that he was “unwilling to corrupt the First Amendment” to ban indecent speech as if it were obscenity.

Thomas has provoked much debate not only for his jurisprudence regarding several areas of free expression but also for his views on the establishment clause of the First Amendment.

In this 1991 photo, Thomas testifies before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington during his confirmation hearings. On the Court, Clarence has consistently railed against restrictions on campaign finance as grossly unconstitutional restrictions on political expression. He has called political speech the “primary object of First Amendment protection.” (AP Photo/John Duricka, File, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

In his concurring opinion in a school voucher decision, Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002), he questioned whether the establishment clause applies to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment. He wrote that “in the context of the Establishment Clause, it may well be that state action should be evaluated on different terms than similar action by the Federal Government.”

Thomas expounded on these views in his concurring opinion in a Pledge of Allegiance decision, Elk Grove Unified School District v. Newdow (2004).

In this opinion, Thomas was more explicit than in Zelman: “I would take this opportunity to begin the process of rethinking the Establishment Clause. I would acknowledge that the Establishment Clause is a federalism provision, which, for this reason, resists incorporation.”

In Utah Highway Patrol Association v. American Atheists (2011), Thomas dissented from the Court’s denial of certiori, emphasizing the the Court needed to “clean up our mess” in the Establishment Clause area.

Thomas’s views on the establishment clause differ dramatically from those of his colleagues. But his jurisprudence in this area — as in other areas of constitutional law — shows him to be a justice not afraid to stand with his own vision.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.