Alabama has among the nation’s strictest eligibility rules for Medicaid.

To qualify for federal Medicaid funding, states are required to cover certain low-income populations, including children, pregnant women, parents of minor children, elderly people, and people with disabilities. The federal government sets baseline eligibility levels, which states can adjust upwards, so the specifics vary by state. Additional federal funding is available when states cover additional populations or extend coverage to those with higher incomes.

Childless adults in Alabama are not eligible for Medicaid, because the state has not expanded Medicaid under the ACA. And parents of minor children are only eligible with extremely low incomes.

Alabama’s current Medicaid eligibility criteria are more limited than many other states. The state’s program covers the following populations (income limits include a built-in 5% income disregard that’s used when determining income-based Medicaid eligibility):

of Federal Poverty Level

You can find information and apply online; submit paper applications by mail, fax or in person to a district office; or call toll-free 1-800-362-1504.

Eligibility: Children up to 141% of FPL; children up to 312% of FPL qualify for CHIP; pregnant women up to 141% of FPL; parents up to 13% of FPL; elderly and disabled individuals with certain medical conditions and income levels

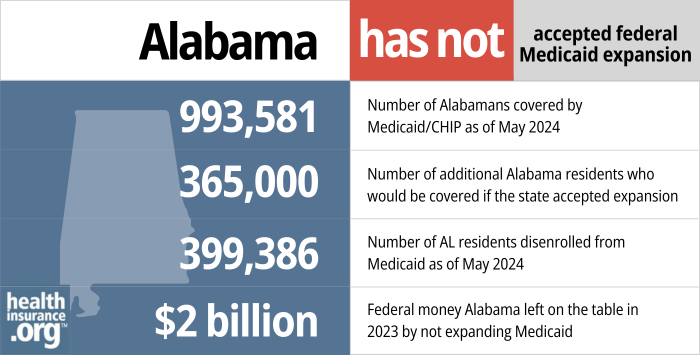

No, Alabama has not accepted federal funding to expand Medicaid under the ACA, despite Democratic lawmakers’ repeated attempts to do so. The Alabama Hospital Association also supports expansion, and has noted that dozens of hospitals in Alabama have closed in recent years or are in danger of closing due to lack of funds. Medicaid expansion would help to keep hospitals in the state afloat, particularly in rural areas.

Estimates vary, but an estimated 300,000 people would gain eligibility for Medicaid in Alabama if the state were to accept federal funding to expand Medicaid (other estimates put this number as high as 340,000). An estimated 128,000 of these individuals are currently in the coverage gap, and have no realistic access to health coverage due to the state’s rejection of Medicaid expansion.

The federal government pays 90% of the cost of Medicaid expansion, and states pay the other 10%. And under the American Rescue Plan, additional funding is available for the first two years of Medicaid expansion.

A 2020 analysis by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation determined that of the 15 states that had not yet expanded Medicaid at that point, Alabama would see the largest decrease in its uninsured rate by expanding Medicaid (as of 2023, there are still 10 states that have not expanded Medicaid or have imminent plans to do so; Alabama is among them). The uninsured rate in Alabama would drop by an estimated 43% if the state were to expand Medicaid.

We’ve created this guide to help you understand the Alabama health insurance options available to you and your family, and to help you select the coverage that will best fit your needs and budget.

Hoping to improve your smile? Dental insurance may be a smart addition to your health coverage. Our guide explores dental coverage options in Alabama.

Use our guide to learn about Medicare, Medicare Advantage, and Medigap coverage available in Alabama as well as the state’s Medicare supplement (Medigap) regulations.

Short-term health plans provide temporary health insurance for consumers who may find themselves without comprehensive coverage.

You have several options for submitting a Medicaid application in Alabama.

Many Medicare beneficiaries receive Medicaid financial assistance that can help them lower Medicare premiums, lower prescription drug costs, and pay for expenses not covered by Medicare – including long-term care.

Our guide to financial assistance for Medicare enrollees in Alabama includes overviews of these programs, including Medicaid nursing home coverage, Extra Help and eligibility guidelines for assistance.

Between March 2020 and March 2023, states received additional federal Medicaid funding due to the COVID pandemic, but were also prohibited from disenrolling people from Medicaid, even if they no longer met the eligibility guidelines. That rule ends March 31, 2023, and states can resume disenrollments as early as April 1.

There is a 12-month “unwinding” period during which states must redetermine eligibility for everyone enrolled in Medicaid. States can begin the unwinding process in February, March, or April 2023. Alabama opted to begin the process in April 2023, and the first round of disenrollments will come at the end of May (for people who are no longer eligible or who fail to respond to a renewal notice).

Alabama Medicaid continued to conduct eligibility redeterminations throughout the COVID pandemic. Disenrollments were not permitted if the person didn’t respond or was found to no longer be eligible. But the state was able to recertify eligibility for many enrollees throughout the pandemic. The state has clarified that most enrollees will keep their regular renewal date, and renewal notices will be spread over a year-long period. So some enrollees won’t hear from Alabama Medicaid until late 2023 or early 2024, and their coverage will continue uninterrupted until their renewal date.

But in some cases, Alabama is also prioritizing renewals for people who are expected to no longer be eligible for Medicaid, so some enrollees will find that their renewal date has changed. Enrollees can find their current renewal date in the My Medicaid portal or call the recipient call center (1-800-362-1504) to talk with a representative and ask about their renewal date.

People who are no longer eligible for Medicaid will need to secure new coverage starting as soon as June 2023 (but for some people, as late as the spring/summer of 2024, depending on their renewal date). This can be through an employer, Medicare, or the health insurance marketplace/exchange, depending on what’s available to them. All of these coverage options have special enrollment periods that allow a person to enroll due to the loss of Medicaid, even if it’s outside of the normal annual enrollment period.

As of late 2022, there were 1,161,239 people enrolled in Alabama Medicaid and CHIP. Since 2013, enrollment in those programs has grown by 46% in Alabama. Nationwide, enrollment has grown by 61%, driven in large part by Medicaid expansion and the COVID pandemic — including the provision in the Families First Coronavirus Response Act that has prevented states from disenrolling people from Medicaid during the COVID public health emergency. But Alabama’s refusal to expand Medicaid has kept enrollment growth lower than the national average.

In early 2018, Alabama Medicaid published a proposed 1115 waiver that would have implemented a work requirement for Alabama’s existing Medicaid population. The state hosted two in-person public comment periods soon thereafter, and opened a public comment period on the proposal.

Almost all of the comments that the state received were in opposition to the work requirement proposal, and many people pointed out that the waiver proposal was a catch-22 situation: People who complied would have lost Medicaid because they earned too much, and people who didn’t comply would have lost Medicaid due to non-compliance with the work requirement.

In response to the comments, Alabama modified the proposal to allow for up to 18 months of transitional Medicaid coverage for low-income parents whose income increases above the Medicaid eligibility threshold. The modified waiver proposal was submitted to CMS in September 2018, but was still pending federal approval when the COVID pandemic began, and the pandemic made work requirements a non-starter.

Although the Trump administration welcomed states’ proposed Medicaid work requirements, The Biden administration notified states in early 2021 that work requirements were not likely to gain approval and that already-approved work requirement waivers were being reconsidered. Ultimately, the Biden administration revoked approval for all previously approved Medicaid work requirements in 2021. And Alabama withdrew its proposed Medicaid work requirement waiver in February 2021.

Alabama’s proposal was much more strict than the proposals that had been submitted by other states, as it would have required 35 hours of work per week for Medicaid beneficiaries with children aged six or older, and 20 hours per week for those with children under the age of six (there would have been an exemption for a single parent with an infant under 12 months, or for a single parent with a child under age six for whom childcare was unavailable). In contrast, most states that considered Medicaid work requirements simply settled on 20 hours per week.

Alabama is already tied with Texas for having the most stringent Medicaid eligibility guidelines in the country. Non-disabled, non-elderly adults are not eligible at all unless they have minor children. And even then, parents of minor children are only eligible if their income doesn’t exceed 18% of the federal poverty level. For perspective, that’s $373/month in total income for a family of three in 2023. So a single mother earning $500/month and raising two children would not be eligible for Medicaid in Alabama (her kids would be eligible though; eligibility for children extends to households earning up to 146% of the poverty level).

And the state’s proposed waiver would have exempted most of the state’s current Medicaid enrollees from the work requirement, including children, the elderly (age 60 or older), pregnant women, and disabled enrollees. The work requirement would only have applied to the “Parent or Caretaker Relative” (POCR) eligibility category, which is non-disabled parents who qualify for Medicaid based on having extremely low income.

Ironically, a very low-income parent who started to work 35 hours per week (the requirement in the waiver) would have almost immediately lost access to Medicaid in Alabama. Assuming the parent was earning minimum wage ($7.25/hour; former Gov. Bentley signed legislation in 2016 preventing cities in Alabama from raising the minimum wage above the federal level), he or she would earn about $1,015/month before taxes. In order to continue to qualify for Medicaid in Alabama, that parent would have to be supporting a household of 13 or more people, with no additional income.

The waiver proposal noted that the POCR category has grown from under 32,000 people to over 74,000 people since 2013, and clearly, the idea here was to remove low-income parents from the state’s Medicaid rolls. The waiver notes the expectation was that “fewer parents and caretaker relatives will need to rely on Medicaid, and thus the group will decrease in size, due to increased income.”

Alabama’s former Governor, Robert Bentley, received federal approval to transition the state’s Medicaid program to a managed care system involving regional care organizations (RCOs), but the implementation of the program was delayed and Bentley resigned before the program took effect. His successor, Governor Kay Ivey, scuttled the RCO plan, and focused instead on efforts to implement a work requirement for existing Medicaid enrollees

In May 2014, Alabama submitted a Section 1115 demonstration waiver proposal to CMS, called Alabama Medicaid Transformation. The proposal called for Medicaid funds to be distributed on a per-patient basis to regional care organizations (RCOs), most of which would be affiliated with local hospitals. The concept was that the RCOs could use preventive care and early (ie, lower-cost) interventions to keep patients out of the hospital. RCOs that spent less than their per-patient allocation could keep the leftover funds, while those that spent more would have to cover the excess cost themselves.

Since Alabama has not expanded Medicaid, the population slated to be impacted by the new 1115 waiver was mostly pregnant women, children, disabled individuals, and nursing home patients.

In February 2016, CMS approved Alabama’s section 1115 waiver, with the agreement that the federal government would contribute $328 million over three years to fund the transformation process, with the potential to secure another $470 million to supplement payments to RCOs (Alabama had asked for a total of $1 billion to fund Medicaid transformation). Some conditions of the approval included a requirement that the RCO model would not cost the federal government any more than the fee-for-service Medicaid program, along with a requirement that children and pregnant women receive more check-ups, and that Medicaid beneficiaries experience fewer hospitalizations.

The state later requested, and received, federal approval to delay the implementation of the RCO model by one year, with a new scheduled start date of October 2017.

But Bentley resigned amid scandal in April 2017, and his lieutenant governor, Kay Ivey, assumed the governorship. Soon after, Ivey’s Administration announced that they would abandon the RCO model, and the state officially withdrew the waiver in August 2017. In January 2018, Ivey directed the state’s Medicaid Commissioner to draft an 1115 waiver proposal that would implement a work requirement on non-disabled Alabama residents enrolled in Medicaid. That proposal, described above, was submitted to CMS for review in 2018, although the state withdrew it in early 2021, once it became apparent that the Biden administration would not approve work requirements and would revoke work requirement waivers that had already been approved by the Trump administration.

In April 2015, then-Governor Robert Bentley created a 38-member Alabama Health Care Improvement Task Force. And in November 2015, the Task Force recommended unequivocally that Alabama should expand Medicaid.

The task force recommended that Bentley and the Legislature “move forward at the earliest opportunity to close Alabama’s health coverage gap with an Alabama-driven solution.” They noted that expanding Medicaid would make coverage newly available to 185,000 low-income residents in the state, and would greatly improve their access to healthcare (note that other estimates have put the number considerably higher than this, at more than 300,000 people).

The week before the task force officially recommended Medicaid expansion, Bentley had said that Alabama was “looking at” the possibility of expanding Medicaid, but he noted that it would be an uphill battle to obtain the funding needed without a tax hike, and the legislature isn’t likely to approve a significant tax increase for anything, including Medicaid expansion. One of the possibilities that the task force considered was a 75 cent/pack tobacco tax to help fund Medicaid expansion.

And although Bentley at least entertained the idea of Medicaid expansion, he was more focused on implementing the RCO transformation (details above) rather than working to expand Medicaid at the same time.

Medicaid expansion was a point of differentiation in the November 2014 governor’s race. Democratic challenger Parker Giffith criticized Gov. Robert Bentley for his opposition to expansion, while Bentley repeatedly reaffirmed his decision during the campaign and immediately following his re-election. However, by late December of 2014, Bentley said he’d be open to a block grant or some other form of federal Medicaid funding to expand health coverage in the state.

In July 2015, a new report from the University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health estimated that the state’s portion of the Medicaid expansion costs would be about $222 million a year, starting in 2020 once the state was responsible for 10% of the cost. However, that is dwarfed by the estimated $12 billion in federal funding that Alabama would have received between 2014 and 2020 if they had expanded Medicaid (the state can still expand Medicaid at any time and start to receive federal funding to cover 90% of the cost).

Although critics of the ACA’s Medicaid expansion often contend that expansion incentivizes people to not work, a 2015 Families USA analysis found that the percentage of uninsured working adults has dropped significantly more in states that expanded Medicaid. In states that expanded Medicaid in 2014, there was a 25% reduction in the number of working adults who were uninsured. But in Alabama, there was just a 12% reduction in the percentage of working uninsured adults in 2014.

Alabama’s Medicaid program had been facing an $85 million shortfall in the state’s 2016 budget. Governor Bentley called a special session of the legislature in August 2016 to address the issue; lawmakers were considering a state lottery or the possibility of using money from the BP oil spill settlement to shore up Medicaid funding.

Ultimately, lawmakers settled on funneling $120 million of state’s $1 billion BP settlement to the Medicaid program over the next two years, solving the problem in the short-term. But there was still a long-term problem, as the oil spill settlement funding solution only lasted for two years.

The federal legislation establishing Medicaid was signed into law in 1965. Former Gov. Lurleen B. Wallace established Alabama’s Medicaid program by executive order in June 1967, and operations began Jan. 1, 1970. As of the program’s start date, 253,991 Alabama residents qualified for Medicaid. By the end of 1970, eligibility increased to more than 313,000 people, and the agency employed 45 people. A detailed history is available on the Alabama Medicaid website.

As of late 2013, just prior to the launch of the health insurance marketplaces, Alabama Medicaid covered about 799,000 people. As of December 2022, Medicaid enrollment in Alabama stood at more than 1.1 million people, a 46% increase since 2013.

Nearly all states, including Alabama, contract with managed care organizations to deliver some or all Medicaid benefits. About 85% of Alabama’s Medicaid beneficiaries were enrolled in primary care case management plans as of 2019 according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. The Section 1115 waiver that Governor Bentley secured to transform Alabama’s Medicaid program called for cutting out private health insurers and contracting directly with regional care organizations — mostly run by hospitals — instead. But that program was scrapped by Governor Kay Ivey before it was implemented.

In August 2015, Governor Bentley cut off Medicaid’s reimbursement arrangement with Planned Parenthood, following a series of undercover videos created by anti-abortion groups alleging that Planned Parenthood was selling fetal tissue. Over the previous two years, Alabama Medicaid had paid Planned Parenthood less than $5,000; all of it was for office visits and contraceptives — no Medicaid funds had been used for abortion. Planned Parenthood sued the state over the termination of reimbursements, and ultimately won. By December 2015, Planned Parenthood was once again on the state’s Medicaid provider list, and the state had been ordered to pay Planned Parenthood’s $51,000 in legal fees.

The US Department of Justice announced in late 2022 that Alabama Medicaid would no longer deny coverage of Hepatitis C medications for Medicaid enrollees with substance use disorders.

Louise Norris is an individual health insurance broker who has been writing about health insurance and health reform since 2006. She has written dozens of opinions and educational pieces about the Affordable Care Act for healthinsurance.org.